This page is for documenting the history of Negro League Baseball that relates to Arkansas.

Note that some Negro League baseball in Arkansas was professional, and some was amateur. However, the line between the two is often blurry. For this reason, Negro League Baseball has been given it's own category on the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

Table of Contents

History

Because the subject was rarely covered by the white press in Arkansas, it's difficult to trace the history of black baseball in Arkansas. To a great extent, black baseball in Arkansas seems to have developed parallel to white baseball in Arkansas. It first became widespread in the late 1860s and early 1870s, developing into a professional game by the 1890s. On rare occasions, local newspapers did indeed mention the African-American side of the game, giving a small glimpse into this realm of baseball. For instance, the Fort Smith Weekly Herald made mention on October 10th, 1868 that, "We understand that boys, white and black, are much given to Base Ball, on Sunday, to the annoyance of many persons in our city, and in violation of the Sabbath. It should be stopped."1 This form of interracial youth baseball in the game's early years was also recalled by Ed Allen of Des Arc, AR, a black Arkansan who was born into slavery and mentioned playing with white boys in that era. On other occasions, local white presses mentioned black baseball in only the most extreme of cases. One such example comes from 1873 when a young boy on an African-American baseball team was killed after he was struck with a bat during a game. Another comes from 1884 when a game between two Little Rock Negro teams, the Reds and the Browns, ended in a fight. Not all reports of black baseball were negative though. The first known example of a black baseball game being reported by the white press in Arkansas was published in the Arkansas Gazette on August 14th, 1885. The game was played between the Reds and the Cadets and resulted in a 25-18 Reds victory. But this media coverage was not typical, and the story of Arkansas' Negro baseball teams during the 19th century remains mostly unknown.

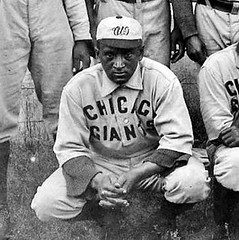

By the turn of the century, black baseball in Arkansas became a popular spectator sport with considerable attention from the white press. The Hot Springs Arlingtons and the Little Rock Quapaws began playing in the late 1890s and and continued through about 1904, playing regional opponents from St. Louis, Kansas City, Memphis and around Texas. The Arlingtons incorporated several black professionals, including future Hall of Famer Rube Foster. Another was David Wyatt, who later became a well-know African-American sportswriter and provided much of the available historical information on the Arlingtons and this era of black baseball in Arkansas. Wyatt was also a key figure in another significant event in Arkansas' black baseball history. In the spring, of 1901, Wyatt was living and working in Hot Springs, AR. Also in the city at the time were John McGraw, manager of the Baltimore Orioles, and Negro league player Charlie Grant. McGraw, noticing Grant's fine baseball skills, attempted to sign him to a contract with the Orioles. However, McGraw, knowing Grant would not be allowed into the all-white major leagues, created a scheme with Wyatt's help to give Grant the alias of a Native-American named Tokohama. The plan fell through, and Grant was never allowed to play in the major leagues on account of his African-American heritage.

Elsewhere in Arkansas, other players were feeling the burden of Jim Crow in baseball too. Near College Hill, AR, a Negro team from Texarkana was punished after playing baseball on a Sunday in 1906. Arrested and jailed, the team was forced to work on the county roads for $1 a day, having no money to pay their fines. But black baseball as a whole was by no means in despair. Rather, black baseball soon began to develop into one of the nation's largest black enterprises. For example, The Freeman, an African-American newspaper based in Indianapolis, IN, began covering the baseball events coming out of Arkansas around 1910. The paper revealed something of a black baseball renaissance in the state. Games were reported from cities across Arkansas, including Little Rock, Hot Springs, Malvern, Arkadelphia, Marianna, and Helena. These teams proved to have significant talent too. Many black Arkansans were soon given opportunities to play elsewhere in the country in the newly developing Negro Leagues. Arkadelphia, AR in particular produced many professionals, including Harry Kenyon, Darltie Cooper, Anthony Cooper, Connie Rector, and five of the Spearman brothers. But perhaps Arkansas' most successful Negro leaguer from this period was Floyd "Jelly" Gardner, who spent more than 16 years in the Negro Leagues from 1917-1933 and was named to the 2006 Special Negro League Committee Hall of Fame ballot.

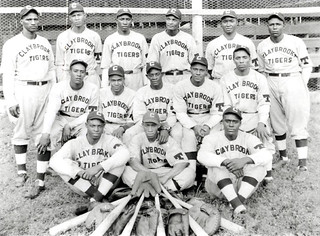

In the 1930s, several teams in Arkansas began playing in the region's top professional Negro Leagues. In 1931, the Little Rock Greys joined the Negro Southern League, and returned for the 1932 season. However, it was in the northeast section of the state near the Mississippi River that a team from the small logging town of Claybrook, AR became the most successful Negro League club ever from Arkansas. By 1933, the Claybrook Tigers were considered the "Semi-Pro Champions of the South"2 . The team's success as independent club helped them gain entry into the Negro Southern League in 1935 and 1936. During those years, Claybrook fielded what is likely the best collection of negro players in Arkansas history.

Black baseball fans in Hot Springs also had something to be excited about during the 1930s. Some of the nation's leading Negro League teams, including the Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords came to the city to host their spring training camps. Numerous Hall of Fame greats, such as Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Jud Wilson and Judy Johnson were among those to train in Hot Springs during this era.

As the decade turned to the 1940s, Negro baseball everywhere was hindered by the World War at hand. Towards the end of the war, however, baseball figures in Little Rock regrouped, and the Little Rock Black Travelers were formed. True to their name, the Black Travelers played at Travelers Field, home of the team's white minor league counterparts. The club joined the Negro Southern League that season, but moved to Richmond, VA in late July with a losing record. After the war ended, semi-pro Negro teams sprang up around the state. For example, the Fort Smith Eagles, Pine Bluff Bear Cats, and Helena Eagles each played respectable schedules. However, as Jackie Robinson and others began integrating the white professional leagues, the Negro leagues began a steady decline into obscurity.

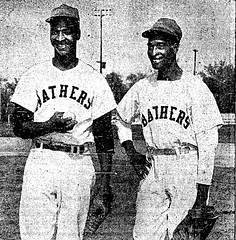

Jim Crow remained a fixture in Arkansas baseball for years afterward. In 1953, the white Hot Springs Bathers in the Cotton States League signed two African-American brothers, Jim and Leander Tugerson. A well-publicized controversy ensued, and in fear of being dropped from the league, Hot Springs sent the two pitchers to play with Knoxville instead. By May, Hot Springs recalled the Tugerson brothers, and on the 20th, scheduled Jim as a starting pitcher. However, just as the game was set to begin, Tugerson was ruled ineligible to play on account of his race, and Hot Springs was forced to forfeit. The Tugerson brothers were ultimately never allowed to play for the Bathers. Notwithstanding, the color barrier in Arkansas baseball was finally broken a year later when Uvoyd Reynolds appeared with Hot Springs on July 20th, 1954, becoming the first African-American to play minor league baseball in Arkansas. Some Arkansas teams followed Hot Springs' example, other did not. The Arkansas Travelers did not integrate until 1963 when future big league MVP Dick Allen starred with the club. Yet even later, the University of Arkansas Razorbacks baseball team finally integrated in 1976 with the inclusion of players Arvis Harper and Hank Thompson.

Note that some Negro League baseball in Arkansas was professional, and some was amateur. However, the line between the two is often blurry. For this reason, Negro League Baseball has been given it's own category on the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

Table of Contents

| Negro League Baseball People |

| Negro League Baseball Teams |

| Negro League Baseball Leagues |

| Negro League Baseball Places |

| Negro League Baseball Spring Training |

| Negro League Baseball Miscellany |

History

Because the subject was rarely covered by the white press in Arkansas, it's difficult to trace the history of black baseball in Arkansas. To a great extent, black baseball in Arkansas seems to have developed parallel to white baseball in Arkansas. It first became widespread in the late 1860s and early 1870s, developing into a professional game by the 1890s. On rare occasions, local newspapers did indeed mention the African-American side of the game, giving a small glimpse into this realm of baseball. For instance, the Fort Smith Weekly Herald made mention on October 10th, 1868 that, "We understand that boys, white and black, are much given to Base Ball, on Sunday, to the annoyance of many persons in our city, and in violation of the Sabbath. It should be stopped."1 This form of interracial youth baseball in the game's early years was also recalled by Ed Allen of Des Arc, AR, a black Arkansan who was born into slavery and mentioned playing with white boys in that era. On other occasions, local white presses mentioned black baseball in only the most extreme of cases. One such example comes from 1873 when a young boy on an African-American baseball team was killed after he was struck with a bat during a game. Another comes from 1884 when a game between two Little Rock Negro teams, the Reds and the Browns, ended in a fight. Not all reports of black baseball were negative though. The first known example of a black baseball game being reported by the white press in Arkansas was published in the Arkansas Gazette on August 14th, 1885. The game was played between the Reds and the Cadets and resulted in a 25-18 Reds victory. But this media coverage was not typical, and the story of Arkansas' Negro baseball teams during the 19th century remains mostly unknown.

By the turn of the century, black baseball in Arkansas became a popular spectator sport with considerable attention from the white press. The Hot Springs Arlingtons and the Little Rock Quapaws began playing in the late 1890s and and continued through about 1904, playing regional opponents from St. Louis, Kansas City, Memphis and around Texas. The Arlingtons incorporated several black professionals, including future Hall of Famer Rube Foster. Another was David Wyatt, who later became a well-know African-American sportswriter and provided much of the available historical information on the Arlingtons and this era of black baseball in Arkansas. Wyatt was also a key figure in another significant event in Arkansas' black baseball history. In the spring, of 1901, Wyatt was living and working in Hot Springs, AR. Also in the city at the time were John McGraw, manager of the Baltimore Orioles, and Negro league player Charlie Grant. McGraw, noticing Grant's fine baseball skills, attempted to sign him to a contract with the Orioles. However, McGraw, knowing Grant would not be allowed into the all-white major leagues, created a scheme with Wyatt's help to give Grant the alias of a Native-American named Tokohama. The plan fell through, and Grant was never allowed to play in the major leagues on account of his African-American heritage.

Elsewhere in Arkansas, other players were feeling the burden of Jim Crow in baseball too. Near College Hill, AR, a Negro team from Texarkana was punished after playing baseball on a Sunday in 1906. Arrested and jailed, the team was forced to work on the county roads for $1 a day, having no money to pay their fines. But black baseball as a whole was by no means in despair. Rather, black baseball soon began to develop into one of the nation's largest black enterprises. For example, The Freeman, an African-American newspaper based in Indianapolis, IN, began covering the baseball events coming out of Arkansas around 1910. The paper revealed something of a black baseball renaissance in the state. Games were reported from cities across Arkansas, including Little Rock, Hot Springs, Malvern, Arkadelphia, Marianna, and Helena. These teams proved to have significant talent too. Many black Arkansans were soon given opportunities to play elsewhere in the country in the newly developing Negro Leagues. Arkadelphia, AR in particular produced many professionals, including Harry Kenyon, Darltie Cooper, Anthony Cooper, Connie Rector, and five of the Spearman brothers. But perhaps Arkansas' most successful Negro leaguer from this period was Floyd "Jelly" Gardner, who spent more than 16 years in the Negro Leagues from 1917-1933 and was named to the 2006 Special Negro League Committee Hall of Fame ballot.

In the 1930s, several teams in Arkansas began playing in the region's top professional Negro Leagues. In 1931, the Little Rock Greys joined the Negro Southern League, and returned for the 1932 season. However, it was in the northeast section of the state near the Mississippi River that a team from the small logging town of Claybrook, AR became the most successful Negro League club ever from Arkansas. By 1933, the Claybrook Tigers were considered the "Semi-Pro Champions of the South"2 . The team's success as independent club helped them gain entry into the Negro Southern League in 1935 and 1936. During those years, Claybrook fielded what is likely the best collection of negro players in Arkansas history.

Black baseball fans in Hot Springs also had something to be excited about during the 1930s. Some of the nation's leading Negro League teams, including the Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords came to the city to host their spring training camps. Numerous Hall of Fame greats, such as Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Jud Wilson and Judy Johnson were among those to train in Hot Springs during this era.

As the decade turned to the 1940s, Negro baseball everywhere was hindered by the World War at hand. Towards the end of the war, however, baseball figures in Little Rock regrouped, and the Little Rock Black Travelers were formed. True to their name, the Black Travelers played at Travelers Field, home of the team's white minor league counterparts. The club joined the Negro Southern League that season, but moved to Richmond, VA in late July with a losing record. After the war ended, semi-pro Negro teams sprang up around the state. For example, the Fort Smith Eagles, Pine Bluff Bear Cats, and Helena Eagles each played respectable schedules. However, as Jackie Robinson and others began integrating the white professional leagues, the Negro leagues began a steady decline into obscurity.

Jim Crow remained a fixture in Arkansas baseball for years afterward. In 1953, the white Hot Springs Bathers in the Cotton States League signed two African-American brothers, Jim and Leander Tugerson. A well-publicized controversy ensued, and in fear of being dropped from the league, Hot Springs sent the two pitchers to play with Knoxville instead. By May, Hot Springs recalled the Tugerson brothers, and on the 20th, scheduled Jim as a starting pitcher. However, just as the game was set to begin, Tugerson was ruled ineligible to play on account of his race, and Hot Springs was forced to forfeit. The Tugerson brothers were ultimately never allowed to play for the Bathers. Notwithstanding, the color barrier in Arkansas baseball was finally broken a year later when Uvoyd Reynolds appeared with Hot Springs on July 20th, 1954, becoming the first African-American to play minor league baseball in Arkansas. Some Arkansas teams followed Hot Springs' example, other did not. The Arkansas Travelers did not integrate until 1963 when future big league MVP Dick Allen starred with the club. Yet even later, the University of Arkansas Razorbacks baseball team finally integrated in 1976 with the inclusion of players Arvis Harper and Hank Thompson.